The way the story is often told is that Western countries gifted human rights to the world and are the sole guardians of it. It may come as a surprise for some, then, that the international legal framework for prohibiting racial discrimination largely owes its existence to the efforts of states from the Global South.

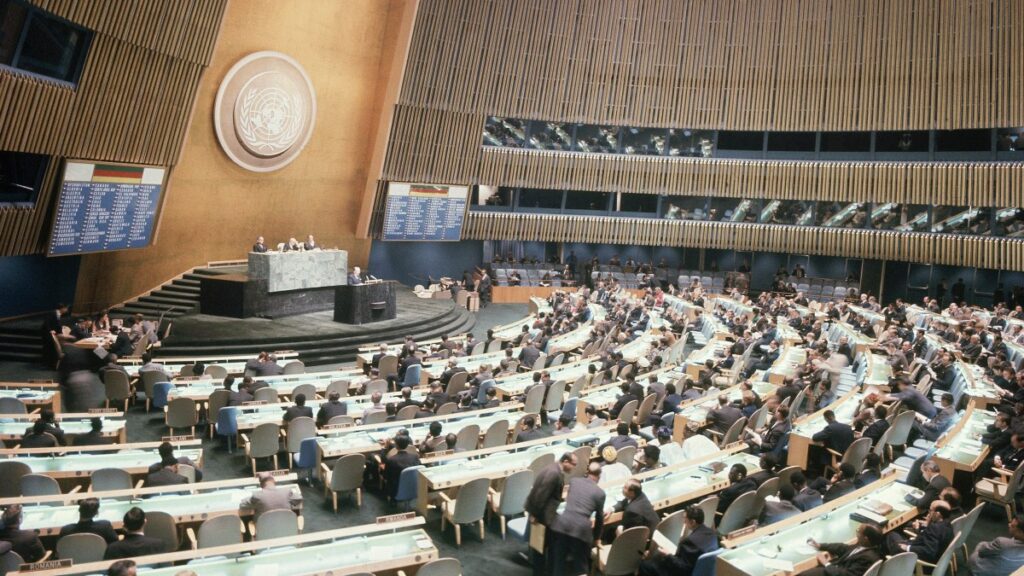

In 1963, in the midst of the decolonisation wave, a group of nine newly independent African states presented a resolution to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) calling for the drafting of an international treaty on the elimination of racial discrimination. As the representative from Senegal observed: “Racial discrimination was still the rule in African colonial territories and in South Africa, and was not unknown in other parts of the world … The time had come to bring all States into that struggle.”

The groundbreaking International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) was unanimously adopted by the UNGA two years later. The convention rejected any doctrine of superiority based on racial differentiation as “scientifically false, morally condemnable and socially unjust”.

Today, as we mark 60 years since its adoption, millions of people around the world continue to face racial discrimination – whether in policing, migration policies or exploitative labour conditions.

In Brazil, Amnesty International documented how a deadly police operation in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas this October resulted in the massacre by security forces of more than 100 people, most of them Afro-Brazilians and living in poverty.

In Tunisia, we have seen how authorities have for the past three years used migration policies to carry out racially targeted arrests and detentions and mass expulsions of Black refugees and asylum seekers.

Meanwhile, in Saudi Arabia, Kenyan female domestic workers face racism and exploitation from their employers, enduring gruelling and abusive working conditions.

In the United States, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives aimed at tackling systemic racism have been eliminated across federal agencies. Raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) targeting migrants and refugees are a horrifying feature of President Donald Trump’s mass deportation and detention agenda, rooted in white supremacist narratives.

Migrants held in detention centres have been subjected to torture and a pattern of deliberate neglect designed to dehumanise and punish.

Elsewhere, Amnesty International has documented how new digital technologies are automating and entrenching racism, while social media offers inadequately moderated forums for racist and xenophobic content. For example, our investigation into the United Kingdom’s Southport racist riots found that X’s design and policy choices created fertile ground for the inflammatory, racist narratives that resulted in the violent targeting of Muslims and migrants.

Even human rights defenders from the Global South face racial discrimination when they have to apply for visas to Global North countries in order to attend meetings where key decisions are made on human rights.

All these instances of systemic racism have their roots in the legacies of European colonial domination and the racist ideologies on which they were built. This era, which spanned nearly four centuries and extended across six continents, saw atrocities that had historical consequences – from the erasure of Indigenous populations to the transatlantic slave trade.

The revival of anti-right movements globally has led to a resurgence of racist and xenophobic rhetoric, a scapegoating of migrants and refugees, and a retrenchment in anti-discrimination measures and protections.

At the same time, Western states have been all too willing to dismantle international law and institutions to legitimise Israel’s genocide against Palestinians in Gaza and shield Israeli authorities from justice and accountability.

Just as the creation of the ICERD was driven by African states 60 years ago, Global South countries continue to be at the forefront of the fight against racial oppression, injustice and inequality. South Africa notably brought the case against Israel at the International Court of Justice and cofounded The Hague Group – a coalition of eight Global South states organising to hold Israel accountable for genocide.

On the reparations front, it is Caribbean and African states, alongside Indigenous peoples, Africans and people of African descent, that are leading the pursuit of justice. The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has been intensifying pressure on European governments to reckon with their colonial past, including during a recent visit to the United Kingdom by the CARICOM Reparations Commission.

As the African Union announced 2026-36 the Decade of Reparations last month, African leaders gathered in Algiers for the International Conference on the Crimes of Colonialism, at which they consolidated demands for the codification of colonialism as a crime under international law.

But this is not enough. States still need to confront racism as a structural and systemic issue, and stop pretending slavery and colonialism are a thing of the past with no impact on our present.

Across the world, people are resisting. In Brazil, last month, hundreds of thousands of Afro-Brazilian women led the March of Black Women for Reparations and Wellbeing against racist and gendered historic violence. In the US, people fought back against the wave of federal immigration raids this year, with thousands taking to the streets in Los Angeles to protest and residents of Chicago mobilising to protect migrant communities and businesses against ICE raids.

Governments need to listen to their people and fulfil their obligations under ICERD and national law to protect the marginalised and oppressed against discrimination.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.